Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos (c. 570 – c. 495 BC) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His political and religious teachings were well known in Magna Graecia and influenced the philosophies of Plato, Aristotle, and, through them, Western philosophy. Knowledge of his life is clouded by legend, but he appears to have been the son of Mnesarchus, a seal engraver on the island of Samos. Modern scholars disagree regarding Pythagoras's education and influences, but they do agree that, around 530 BC, he travelled to Croton, where he founded a school in which initiates were sworn to secrecy and lived a communal, ascetic lifestyle. This lifestyle entailed a number of dietary prohibitions, traditionally said to have included vegetarianism, although modern scholars doubt that he ever advocated for complete vegetarianism.

The teaching most securely identified with Pythagoras is metempsychosis, or the "transmigration of souls", which holds that every soul is immortal and, upon death, enters into a new body. He may have also devised the doctrine of musica universalis, which holds that the planets move according to mathematical equations and thus resonate to produce an inaudible symphony of music. Scholars debate whether Pythagoras developed the numerological and musical teachings attributed to him, or if those teachings were developed by his later followers, particularly Philolaus of Croton. Following Croton's decisive victory over Sybaris in around 510 BC, Pythagoras's followers came into conflict with supporters of democracy and Pythagorean meeting houses were burned. Pythagoras may have been killed during this persecution, or escaped to Metapontum, where he eventually died.

In antiquity, Pythagoras was credited with many mathematical and scientific discoveries, including the Pythagorean theorem, Pythagorean tuning, the five regular solids, the Theory of Proportions, the sphericity of the Earth, and the identity of the morning and evening stars as the planet Venus. It was said that he was the first man to call himself a philosopher ("lover of wisdom") and that he was the first to divide the globe into five climatic zones. Classical historians debate whether Pythagoras made these discoveries, and many of the accomplishments credited to him likely originated earlier or were made by his colleagues or successors. Some accounts mention that the philosophy associated with Pythagoras was related to mathematics and that numbers were important, but it is debated to what extent, if at all, he actually contributed to mathematics or natural philosophy.

Pythagoras influenced Plato, whose dialogues, especially his Timaeus, exhibit Pythagorean teachings. Pythagorean ideas on mathematical perfection also impacted ancient Greek art. His teachings underwent a major revival in the first century BC among Middle Platonists, coinciding with the rise of Neopythagoreanism. Pythagoras continued to be regarded as a great philosopher throughout the Middle Ages and his philosophy had a major impact on scientists such as Nicolaus Copernicus, Johannes Kepler, and Isaac Newton. Pythagorean symbolism was used throughout early modern European esotericism and his teachings as portrayed in Ovid's Metamorphoses influenced the modern vegetarian movement.

Teachings

Numerology

According to Aristotle, the Pythagoreans used mathematics for solely mystical reasons, devoid of practical application. They believed that all things were made of numbers. The number one (the monad) represented the origin of all things and the number two (the dyad) represented matter. The number three was an "ideal number" because it had a beginning, middle, and end and was the smallest number of points that could be used to define a plane triangle, which they revered as a symbol of the god Apollo. The number four signified the four seasons and the four elements. The number seven was also sacred because it was the number of planets and the number of strings on a lyre, and because Apollo's birthday was celebrated on the seventh day of each month. They believed that odd numbers were masculine, that even numbers were feminine, and that the number five represented marriage, because it was the sum of two and three.

Ten was regarded as the "perfect number" and the Pythagoreans honored it by never gathering in groups larger than ten.Pythagoras was credited with devising the tetractys, the triangular figure of four rows which add up to the perfect number, ten. The Pythagoreans regarded the tetractys as a symbol of utmost mystical importance.Iamblichus, in his Life of Pythagoras, states that the tetractys was "so admirable, and so divinised by those who understood [it]," that Pythagoras's students would swear oaths by it.Andrew Gregory concludes that the tradition linking Pythagoras to the tetractys is probably genuine.

Modern scholars debate whether these numerological teachings were developed by Pythagoras himself or by the later Pythagorean philosopher Philolaus of Croton. In his landmark study Lore and Science in Ancient Pythagoreanism, Walter Burkert argues that Pythagoras was a charismatic political and religious teacher,but that the number philosophy attributed to him was really an innovation by Philolaus. According to Burkert, Pythagoras never dealt with numbers at all, let alone made any noteworthy contribution to mathematics.Burkert argues that the only mathematics the Pythagoreans ever actually engaged in was simple, proofless arithmetic, but that these arithmetic discoveries did contribute significantly to the beginnings of mathematics.

Attributed discoveries

In mathematics

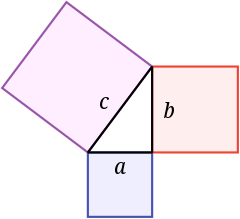

Although Pythagoras is most famous today for his alleged mathematical discoveries, classical historians dispute whether he himself ever actually made any significant contributions to the field.Any mathematical and scientific discoveries were attributed to Pythagoras, including his famous theorem, as well as discoveries in the fields of music, astronomy, and medicine. Since at least the first century BC, Pythagoras has commonly been given credit for discovering the Pythagorean theorem, a theorem in geometry that states that "in a right-angled triangle the square of the hypotenuse is equal [to the sum of] the squares of the two other sides"[201]—that is,  . According to a popular legend, after he discovered this theorem, Pythagoras sacrificed an ox, or possibly even a whole hecatomb, to the gods. Cicero rejected this story as spurious because of the much more widely held belief that Pythagoras forbade blood sacrifices. Porphyry attempted to explain the story by asserting that the ox was actually made of dough.

. According to a popular legend, after he discovered this theorem, Pythagoras sacrificed an ox, or possibly even a whole hecatomb, to the gods. Cicero rejected this story as spurious because of the much more widely held belief that Pythagoras forbade blood sacrifices. Porphyry attempted to explain the story by asserting that the ox was actually made of dough.

The Pythagorean theorem was known and used by the Babylonians and Indians centuries before Pythagoras, but it is possible that he may have been the first one to introduce it to the Greeks. Some historians of mathematics have even suggested that he—or his students—may have constructed the first proof. Burkert rejects this suggestion as implausible, noting that Pythagoras was never credited with having proved any theorem in antiquity. Furthermore, the manner in which the Babylonians employed Pythagorean numbers implies that they knew that the principle was generally applicable, and knew some kind of proof, which has not yet been found in the (still largely unpublished) cuneiform sources. Pythagoras's biographers state that he also was the first to identify the five regular solids and that he was the first to discover the Theory of Proportions.

No comments:

Post a Comment